Yes, the Democrats Are More Left Than Ever

Using DW-Nominate Scores for Good and Evil

There is a debate raging on X (twitter) right now over whether or not the Democrats have become more left wing or more right wing in recent years. This debate is nothing new; people have been having this debate for as long as there has been a Democratic Party, for as long as there have been any parties in America whatsoever. While there are good critiques to be had about the usefulness of such a division between left and right, borne out of the chaos of the French Revolution, such divisions do exist and can be quantified. Indeed, political scientists have come up with all sorts of ways to divine the ideological trends of the political parties throughout the ages.

One such way of making a quantifiable measurement of ideology is to use what political scientists call the DW-Nominate scores, a standard metric that uses roll call votes of Congressional members and then places that vote on a traditional left or right axis, with a number between -1 (the furthest left) and 1 (the furthest right). For instance, a vote on a budget that increases benefits to poor people would be classed as a left-leaning vote, while a vote against it would be classified as a right-leaning vote. To use a non-economic example, a vote banning background checks in order to be able to purchase guns would be a right-leaning vote while a vote against would be left-leaning. As imperfect as the Left-Right divide is in explaining true political differences (ideology, like gender, like anything else related to the brain is a spectrum and humans are not binary creatures like this; real voters often hold contradictory ideological positions), we can still quantify each vote, and then come up with an average model to determine how Congress as a whole has changed ideologically over the years based on those votes.

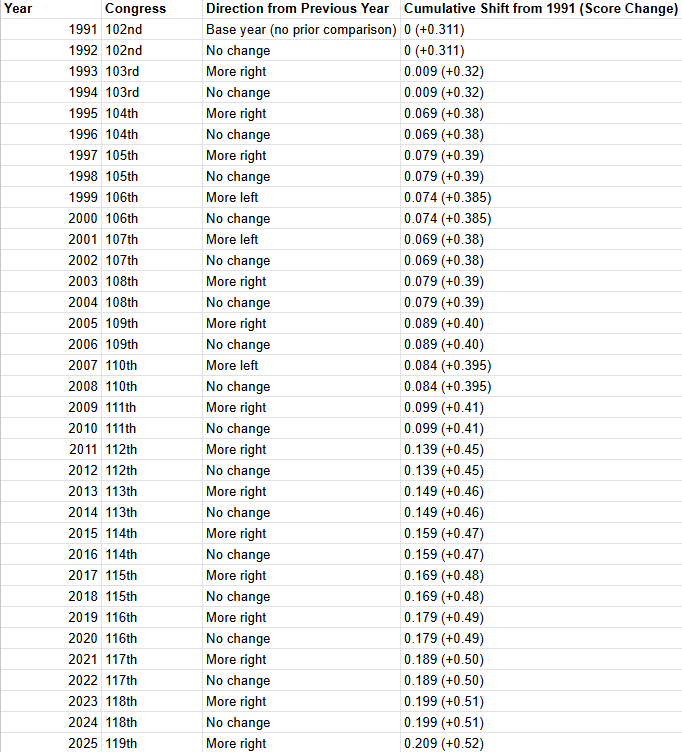

At the 50,000 foot level, we can say that the Republican Party is trending more conservative than the Democratic Party is trending left. However, when we zoom in to a more reasonable timespan, we see just how large the discrepancy is. Using 1991 as the baseline (the end of the Cold War seems as good as a ground-shifting, epoch-defining world event as any, though truly any date can be used as the baseline), we can set -0.311 as the DW-Nominate score that approximates “the Democratic center”. President HW Bush of the Republicans of 1991 had a DW-Nominate score of 0.38, so he would be considered “more conservative” than the average Republican at the time, who had a DW-Nominate score of 0.311 on average.

DW-Nominate Average Scores for Democrats Since 1991

DW-Nominate Average Scores for Republicans Since 1991

The data tells a compelling and clear story: since 1991, Republicans have gotten 0.209 points more conservative, driving their DW-Nominate scores up to 0.52 (remember, this is a number range between -1 and +1, so the closer to -1 or +1 you are, the more extreme you are), while Democrats have barely moved by comparison, from a baseline of -0.311 to -0.41 in the same timespan (in other words, they got -0.099 more left-leaning since 1991.

This doesn’t mean that the parties always accelerated ideologically of course. There were some years when the parties either stagnated (meaning no DW-Nominate changes), or swung (on average) in the opposite direction. For instance, for Democrats, passing the ACA and Stimulus Act in 2009 required compromises to the right, which resulted in the average score for their members increasing. Conversely, Republicans losing the 2007 midterms lost them a lot of moderate members, but on average, their membership did get less extreme that year.

It’s Just Not Fair (For The Left)

Let’s call a spade for what it is: it isn’t fair that Republicans not only get away with becoming more right wing over time, but also go on to consistently win elections. For instance, their most conservative majority came in 2025, led by their most extreme standard-bearer in history in the form of Donald Trump. Meanwhile, Democrats flirt with going more Left in response to Republican extremism, but there is a stronger anti-extremist bias on average in the Democratic Party than there is in the Republican Party. Looking at the trendline over time and comparative scores, the Democrats of today are as extreme as the Republicans of 2009 were (-0.41 and +0.41, respectively). As an aside, Democrats in 2009 were as extreme as Gingrich’s 1994 revolution!

If it was just the case that voters rewarded partisan centrism and punished ideological extremism, the Democratic Party, being far closer to the center, should be the party running the country right now. Indeed, that is precisely the viewpoint shared by many centrist pundits, that if Democrats only veered and triangulated further to the center, we could win more votes and thereby more elections.

There’s a reason why the Left is irked by this notion. First, they see how extreme the Republican Party has gotten, alongside getting most of their political wishlist accomplished (from banning abortion to tax cuts), and witnessing in disgust how they’ve been rewarded by the American public with even more power. Conversely, they see a Democratic Party chasing polls, moderating and triangulating further and further, and losing more and more elections as a result. While it is true that Democrats did get more left-leaning since 2016, really since 2010, the pace at which they did so was far outpaced by the Republicans embrace of their ideological extremes. Correlation here isn’t causation, of course. Democrats didn’t lose elections because they chased polls or because they moderated too much or not enough.

Candidate quality matters just as much as candidate policy, and when the leader of your party rambles for 90 minutes in front of tens of millions of voters about “beating Medicare”, then yeah, your party is going to do a lot worse than the other party.

That all being said, there is real anger amongst the party base and activists. For all the whimpering about the party becoming more left, it still is only as extreme (in both policy and tactics) as the GOP of 2009. We live in a world where judicial fiat has made abortion illegal, and where the Republican Congress has made no effort to overturn this judicial overreach. At the same time, we live in a world where healthcare is getting more expensive even if you have employer-provided insurance, where access to any healthcare is getting more difficult, yet at the same time, we still don’t have a consensus in the Democratic Party that making healthcare universally cheaper (even up front cost-free) or more accessible is a good idea. This doesn’t mean passing Medicare For All, this just means reforming, by any means, US healthcare away from the status quo; Democrats don’t even have an agreement on that.

We’re All Just Along For The Ride

Voters in 2025 expect and respect extremist candidates; or, to put it in a more massaged framing: voters respect the candidates who stand up and fight for what they believe in, and they expect those candidates to be counter to the ideology of the other side. No one in 2025 is going to take someone who just stepped out of a time machine from 2009 seriously, and so it is with Democratic primary voters. At the end of the day, these are the people who are going to decide the future of the Democratic Party. Based on trendlines, these candidates will continue to be more Left-leaning by average than their past counterparts, while still being far-outpaced by the Republican party in terms of extremism.

In a way, it’s sort of pointless to join in the chorus of pundits arguing this way or that for the Party to shift ideologically. After 2024, the people who comprise the Democratic base are pissed at their (comparatively more moderate) party and at the (comparatively much more radical) opposition party. Party primaries after all, aren’t free-for-alls. Outside of the American South and the Upper West, most primaries are closed or have some restriction, meaning only party partisans weigh in on nominations. In the 2026 and 2028 primaries, Democratic voters will nominate a plethora of candidates, and we can already reasonably predict two things:

The nominees will be more left-leaning compared to their DW-Nominate scores in prior years.

Very few voters will make their decisions based on what they hear on the Ezra Klein Show or Welcomefest, or other pundit influencer networks on the Left or the Right.

Will it be enough for them to win? We don’t know yet; no one knows anything about the future other than it is going to happen.

What we can say for certain is that the horse-race will be entertaining to watch, that it will drive eyeballs to articles and ears to podcasts. We can also say it will be immensely consequential, not just for America but for the entire world. Every election in this hegemonic country tends to have similar stakes.

Political Science vs Political Punditry; or, this is all rather pointless, innit?

The essential crux of the debate boils down to a question over what the ideal specific DW-Nominate score for a Democratic Congressional candidate should have for their particular district in their upcoming next election. Should candidates fight fire with fire, and nominate candidates as extreme as the Republicans? Or, is more moderation the order of the day? Using the current DW-Nominate scores for both parties, the member which closely represents the average score for Republicans is Dan Webster of Florida’s (current) 11th district, who has a DW-Nominate of 0.52. For Democrats, at a DW-Nominate score of -0.411, that would be Debbie Wasserman Schultz of Florida’s (current) 25th district.

If trends hold, the incumbent elected in 2026 for the Republicans will be more conservative than Webster and for the Democrats, more liberal than Wasserman Schultz. However, that is in the abstract. Specifically, for each member election in the country, every single candidate will have to determine if they will run to the left or to the right of their party’s average member. And honestly? It will depend on locality and candidate. In more purple/red districts and states, you will likely see candidates run and win on more conservative platforms. However, you might also see some genuine edge cases, where a liberal/left candidate outperforms expectations in a red/purple state and goes on to win, and vice versa.

In other words, outside of winning an online partisan debate for a preferred ideology, there is little benefit in fretting about such an unknowable yet also mostly predictable outcome. If more conservative pundits spent every single day arguing how the Democrats need to nominate candidates that match that ideology or vice versa, would it even sway one election their way? Likely not.

For those who actually have a vaunted stake in elections, for candidates and staffers alike, the best advice any political scientist would give would be to hew close to the ideological expectations of their party. Don’t run, in other words, as a +0.202 candidate in a Democratic primary or as a -.104 candidate in a Republican primary. Beyond that though, it boils down to a question of likability, of finances, of candidate quality. You can be a perfect ideological match for your district yet if you don’t regularly shower, call people slurs every waking minute, and are a general menace to your community, you likely will not win your election, whatever or wherever it is.

And really, the best advice for any candidate building a policy platform is to talk to the voters. The only way to win elections is to match voter expectations, and the only way to meet those expectations is to know what those expectations are, by talking to the voters. Voters aren’t some abstract; they are real people with real concerns, and they will often tell you what they care about. If you say you care about the same things, if you say you agree with the solutions those voters have come up with (whatever they are), then that is a far better campaign strategy than reading and adopting whatever DC policy thinktank has come up with. Governing is different and requires expert expertise, but for electioneering? The voter is king.

Thus, to part with a single maxim:

Convincing only voters wins elections; convincing only thinktanks loses elections; if a choice must be made, always choose the voters.